Making movies. Enjoying movies. Remembering movies.

THE SCREENING ROOM

Related Articles:

More Articles by Rick

Mitchell

|

By Rick Mitchell

Actually, exhibition seems to have a head start on this, finally getting out of their shoebox multiplex mindset and moving toward large auditoriums with big screens. However, otherwise making the theatrical experience more home like seems counterproductive and while the jury is still out on digital projection, the industry could be exploiting existing technology like 70mm. Not by blowing up 35mm anamorphic or spherical films for sound, as was done in the Eighties, but, for the properly selected films, original 65mm photography that would yield razor sharp images on those large screens with a depth and clarity that will take digital years to achieve, if then. But to be really effective, the films have to be shot so that they will look great on such large screens.

In a recent L.A. Times Sunday Calendar article on the decline in attendance, Peter Bogdanovich mentioned encountering a young film student who was not impressed by John Ford's "The Grapes Of Wrath" (1940) until he had had a chance to see it on the big screen, for which Ford and cinematographer Gregg Toland had designed it. While we boomers who grew up during the 1955-70 roadshow era were consciously impressed by the spectacular nature of films like "How The West Was Won" (1962) and "Lawrence Of Arabia" (1962) subconsciously we were also impressed by the depth and clarity of the images from large negatives viewed on large screens, which is why younger people find such films so underwhelming, especially viewed by "letterboxed" video on a laptop.

Through the Seventies, most artists making regular 35mm films for theatrical release envisioned their works as ultimately being seen on the screens of legendary palaces like the Radio City Music Hall and the Chinese and had them staged and composed accordingly. As a result, even Monogram and PRC "Bs" from the Forties look better on the giant screen of the Egyptian when revived there than many contemporary "A" features. (For the record, in the Forties the Chinese did run double bills with the second feature often a Republic, Monogram, or PRC "B.")

Unfortunately, over the last quarter century the production end of the business has developed a "small screen" mindset, what with the increased use of video assists in production as well as post going almost entirely to video-based editing systems. Where in the past directors, cinematographers, and producers of even "C" pictures saw dailies, as well as progressive cuts, in screening rooms, today, even on expensive "A" productions shot on film, the directors and cinematographers often see dailies only on video monitors and donıt see anything projected onto a screen until they see the answer print!

|

Tragically there really are no contemporary films suitable for testing

pro-large dramatic screen filmmaking (as Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC once

commented, trying to do such a film in IMAX is a joke), but we who live

in Hollywood regularly get a chance to get some idea of what such

presentations are like thanks to the Dome's annual Cinerama

presentations and the frequent revival of 65/70mm films from the past by

the American Cinematheque, the Los Angeles Museum of Art, and the

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which ran a new 70mm print

of

"Cleopatra" (1963) on May 15.

The American Cinematheque's most recent 70mm Festival offered an

interesting opportunity to contrast different approaches to filmmaking

for large wide screens with rare screenings of 70mm prints of the second

and third Todd-AO productions, "Around The World In Eighty Days" (1956)

and "South Pacific" (1958).

Like "Oklahoma!" (1955), "South Pacific" was produced by a

conglomeration of Rodgers and Hammerstein, the Todd-AO Corporation, and

a specially formed roadshow distribution company called Magna Theaters,

using the production facilities of 20th Century-Fox, which would later

absorb Magna and take over its contract with Todd-AO. Though he'd

initiated and arranged financing for the development of Todd-AO, Michael

Todd was not allowed involvement with Magna, and this becomes

immediately obvious when you compare the Magna productions to Todd's

personal "Around The World."

Todd had initially been involved with Cinerama and, among other things,

was unhappy with Fred Waller's inability to eliminate the visible joins

between the panels. He set out to develop a "Cinerama Out Of One Hole,"

which Dr. Brian O'Brian of American Optical determined could be achieved

by using a 65mm format from 1930, essentially the same one used for "The

Bat Whispers" (see

http://.in70mm.com/newsletter/2005/70/walt/siegmund.htm) with

wide angle lenses, the image projected onto a deeply curved screen. The

shortest lens for this system, which had an 128mm field-of-view, had

fish-eye type distortions which also created a faux Cinerama-like 3-D

effect and was originally intended to be the key element in the process,

yet neither the Magna executives nor "Oklahoma!" director Fred Zinnemann

liked the distortions. The lens would only be used for a handful of

shots in "Oklahoma!" and apparently had been abandoned by the time of

"South Pacific." (The process' filming speed was also reduced from 30

fps to 24 fps to eliminate the necessity of shooting an additional

version for 35mm general release.) As a result, most of "Oklahoma!" and

all of "South Pacific" are shot primarily like 35mm CinemaScope pictures

of the time, though with more full and medium shots than would be used

today.

While the new print of "South Pacific" is gorgeous for the most part,

suggesting that either the negative is in great shape or photochemical

restoration has reached new highs, all in all another accolade for

Schawn Belston of Fox, I personally have to admit that I can't

understand the popularity of this film at the time of its release. It's

a rather strange subject for a musical, episodic with little setup, and

its tone is all over the place. (This may be due to the fact that this

was the 150 minute general release version; a faded 70mm print of the

original roadshow version was shown following the restored print but I

couldnıt stay for it.) The sound, converted to DTS' 6 track digital

format, was terrific, beautifully capturing every note of Alfred

Newman's adaptation and conducting of the score. It was so good that the

singing voice doubles for Rossano Brazzi and John Kerr were all too

obvious. "South Pacific" appears to be the first Fifties 65mm film to

make extensive use of matte paintings, by Emil Kosa, Jr., and

miniatures, some incorporated via split screens, most of which hold up

surprisingly well. (L.B. Abbott, ASC supervised the effects work.) As

for the infamous color filters, well, Leon Shamroy, ASC does make up for

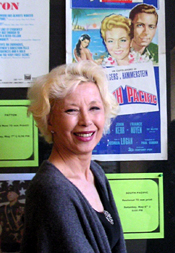

them in his exquisite close-ups of then 17 year old France Nuyen, who

introduced the Egyptian screening. (Again, for the record, all three

original Todd-AO features had their reserved-seat Los Angeles

engagements at the Egyptian. The "80 Days" Egyptian run was its '68

re-issue; the original run played the Carthay Circle.)

|

|

France Nuyen from "South Pacific" |

"South Pacific" looked great, but was still not as impressive on the

giant Egyptian screen as the fading 1968 print of "Around The World"

shown the previous night. Controlled by Todd, the film was clearly

designed to really exploit the 65/70mm format in a way that only a

handful of later films like "Lawrence Of Arabia," the race scenes in

"Grand Prix" (1966) and Robert Wise's three in the format would.

"Around The World" is clearly influenced by "This Is Cinerama" (1952)

and possibly "Cinerama Holiday" (1955), not only in its scenic POV

shots, but in the dramatic scenes as held. Though Todd supposedly was

not to happy with some of the more "folksy" stuff Merian C. Cooper and

Lowell Thomas added to the second half of "This Is Cinerama," Todd did

respond to its effect on audiences and took the proper lighthearted

approach to the "book" portions of his film, with a lot of help from

humorist S.J. Perelman, who was responsible for much of its "veddy

British" satire. Overall the film is actually very intelligently written

and played with the right touch so that it doesnıt come off as campy. As

for the cameos, aside from the Jose Greco dance troupe number, only the

Marlene Dietrich/ George Raft/ Frank Sinatra bits in the San Francisco

sequence seem to have been specifically concocted for them; the other

cameos come naturally out of the plot and therefore do not annoy

contemporary audiences who may not be familiar with the particular

actors.

I suppose Todd can be credited overall for the film's visual look and

editing, with most scenes played in medium or wider shots, most of which

are photographed with shorter focal length lenses which allow you to see

a tremendous amount of detail in the sets and locations, enhancing the

feeling of being in the picture far more than is possible with long

lenses. In fact, the few tight close-ups, such as in the Hong Kong

sequence where Robert Newton has Cantinflas' drink spiked, and the first

appearance of the steward played by Peter Lorre really stand out thanks

to their contrast to the wider views in the rest of the film. This is

something that really works best in big screen presentations and can

also be experienced with 35mm anamorphic productions from the Fifties

and Sixties that emphasized the use of shorter lenses, but large

negative origination adds a visual dynamic range that 35mm cannot match

(and forget Super 35).

Unfortunately, too many of today's filmmakers are more concerned with

the video than the theatrical release. Granted, the former yields the

greater financial return, but the success in that market is founded on

the filmıs success in the latter. Since older films have proven to be as

successful in home video as more recent video friendly projects, there

is no reason to assume that tailoring a film for theatrical presentation

will hurt its chances in video if it's really successful in theaters.

|

|

Head Projectionist at the Egyptian, Paul Rayton |

However a new film taking this approach will probably have to come from

a source outside the mainstream industry, as Cinerama and Todd-AO did,

but with the right subject matter, it could be a sleeper and actually

doesnıt need to cost $100,000,000+. But its subject matter needs to be

something that stimulates a desire in at least the contemporary 15-30

year old demographic to want to see it in a theater, not a repeat of the

mistake that doomed the attempted 65mm revival of the Nineties with "Far

And Away" (1992) and "Hamlet" (1996).

These films were influenced by the publicity for Robert A. Harris'

restoration of "Lawrence Of Arabia," considered the ultimate "cerebral

epic." What was ignored was that in the intervening years, such material

had increasingly become associated with TV fare like "Masterpiece

Theater" and those Robert Halmi Hallmark specials. To reacquaint

contemporary audiences with the higher image quality of 65mm, it needed

to be used on films like "Speed" (1994), "Independence Day" (1996),

"Twister" (1996), or "Titanic" (1997). Though a surfeit of badly done

films of this type has reduced their audience appeal in recent years, a

reasonably fresh project done with respect to the audience, designed for

the BIG screen, and shot in 65mm, does have a great chance for success.

Rick Mitchell is a film editor, film director, and film historian. He lives in Los Angeles.

İ 2006 Rick Mitchell. All rights reserved.

IMAGES: İ 20th Century Fox; Michael Coate. All rights reserved.