Making movies. Enjoying movies. Remembering movies.

| Posted February 15, 2005 |

|

DVD Decision 2004

Second Wave Of Online Petition Titles Released |

By

Bill Desowitz

|

|

|

|

|

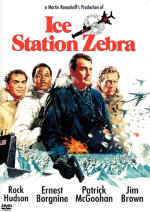

The

five winners of DVD Decision 2004, the second online promotion from

Warner Home Video and Turner Classic Movies, in which movie fans cast

their votes for their most anticipated classics on DVD, are now

available: “The Letter” (1940), “Random Harvest" (1942), "King Solomon’s

Mines” (1950), “Ivanhoe" (1952), and "Ice Station Zebra” (1968).

It’s an eclectic, entertaining mix of romance, melodrama and adventure,

divided between Warner Bros. and MGM titles, and all five look

magnificent on disc. Not surprisingly, “The Letter” and “Random

Harvest” hold up for their subtle, intimate craftsmanship and emotional

resonance, while “King Solomon’s Mines” and “Ivanhoe” are absorbing in

their own right. Meanwhile, “Ice Station Zebra,” the Cold War

submarine thriller shot in Super Panavision 70, which Howard Hughes

called his favorite movie, is still a guilty pleasure despite its chilly

moments.

Director William Wyler seems particularly inspired by “The Letter,” an

early, exotic noir and reworking of the Somerset Maugham play that

reunited him with Bette Davis after “Jezebel.” Although it

contains one of the most powerful openings in movie history – a man

stumbles down the steps of a veranda, followed by Davis, who pumps

several gunshots into him and then coolly drops the gun – the ending is

just as stunning for its hypnotic mood and visual elegance, even though

it is marred by silly Production Code tampering.

Davis plays the bored wife of Herbert Marshall, the meek manager of a

rubber plantation in Malaya, who murders her secret lover when she

discovers that he is married to a Eurasian (Gale Sondergaard.

Davis tries to cover up her crime by claiming self-defense, but then is

forced to buy back an incriminating letter from the widow. Her

lawyer and family friend (brilliantly played by newcomer James

Stephenson, who tragically died of a heart attack a year later) becomes

the film’s moral compass, who is both attracted to and repelled by

Davis’ wicked charm. For her part, Davis is fascinating in her

unsympathetic role.

Apparently it was Wyler’s idea to cast Davis in moonlight to underscore

her suppressed guilt. He further enhanced the visual emblem by

using louvered blinds on the windows to print prison stripes on her like

a Scarlet Letter. Director and star bitterly fought over the final

confrontation between Davis and Marshall, in which he forgives her and

wants to start anew and she confesses: “I still love the man I killed.”

It seems that the star refused to look him in the eye and stormed off

the set. Wyler prevailed and the result is arguably Davis’ best

performance. Interestingly, the DVD contains an alternate ending

without the final confrontation between husband and wife. Needless

to say, it severely softens the blow. Too bad they didn’t shoot an

alternate ending to defy the Production Code.

Ronald Coleman, one of the few urbane actors to make the transition from

silents to talkies, nonetheless didn’t possess the warmest of personas,

yet was at his most charming and vulnerable in “Random Harvest,” one of

the best amnesia love stories ever made, directed with literate grace by

Mervyn LeRoy and produced by Sidney Franklin. But then, Greer

Garson often brought out the best in her male co-stars. Based on

the novel by James Hilton, where “Lost Horizon” meets “Goodbye, Mr.

Chips” in another ephemeral bliss, Coleman wanders out of an English

asylum in both a literal and figurative fog, just as the Armistice is

announced. He bumps into Garson, a music hall performer with

enough maternal love to nurse anyone back to health, and before you know

it, they’re married with a son in a sweet cottage in the country, when,

suddenly, they’re momentarily parted just as Coleman regains his

confidence, and an accident returns his memory and he’s back to his

dull, privileged, upper class life.

Then something truly bold happens when Garson slips anonymously back

into Coleman’s life in a subservient role just to be near him again.

Little by little, déjà vu kicks in, and she patiently and then

desperately tries to help him recapture their fleeting love. It’s

a delicate balancing act, of course, and the two stars pull it off

marvelously.

“King Solomon’s Mines” offers not only sprawling adventure but also the

dashing Stewart Granger as the famous hunter Allan Quartermain, lured

into deepest Africa by the flaming Deborah Kerr in search of her missing

husband and legendary treasure. Yet there is a melancholy tinge

that lies at the heart of Granger’s existential struggle, typified by

that wonderful moment when he shows Kerr miraculous life in the forest

by turning over a fallen tree, where thousands of bugs crawl underneath

a rotting limb. In Swahili, Granger says, “You eat me. I eat you.

We eat them. They eat us. Survival of the fittest.” In

some ways it’s more memorable than the incredible stampede that was shot

as an afterthought while they were on location. Speaking of which,

Robert Surtees’ Technicolor cinematography on location is gorgeous.

Speaking of somber, Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” is a lot more serious

swashbuckler about the fight between the Normans and Saxons than the

younger and more popular “Robin Hood” legend. Here, Ivanhoe

(played by the handsome and stoic Robert Taylor) returns from the

Crusades to raise a ransom for King Richard the Lionhearted, held

captive in Austria. Disowned by his father (Finlay Currie), still

in love with Lady Rowena (Joan Fontaine, sister of Olivia DeHavilland,

oddly enough, from “The Adventures Of Robin Hood,” 1938), Ivanhoe

promises that King Richard will treat the Jews of England more humanely

if they help return him to the throne. He even appeals to Isaac of

York (Felix Aylmer) for financial assistance, whose daughter (Elizabeth

Taylor) quickly becomes smitten with him. This evil Prince John

(Guy Rolfe) is a lot more intense than Claude Rains, his counterpart in

“Robin Hood,” but, surprise, surprise, George Sanders steals the show as

the sensitive knight, Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert. It’s a rousing

adventure, aided, among other things, by Freddie Young’s beautiful

Technicolor cinematography (shot on location in England), Alfred Junge’s

lavish art direction and Miklos Rozsa’s fiery score.

While neither as crafty as “The Guns Of Navarone” (1961) nor as pulpy as

“Where Eagles Dare” (1969, “Ice Station Zebra” nonetheless holds a

special, stoic place in the Alistair MacLean canon as a popcorn picture.

It takes itself way too seriously, though, perhaps because of its Cold

War relevance, yet director John Sturges just doesn’t have the kind of

inspiring material as he had with “Bad Day At Black Rock” (1955), “The

Great Escape” (1963), or “The Magnificent Seven” (1960). Still, as

submarine adventures go, this is quite a nail biter, as Rock Hudson

(terribly wasted) commandeers a nuclear sub to check out an abandoned

weather outpost at the North Pole, completely unaware of the global

peril that awaits them. It’s a pretty edgy group, ranging from

trigger happy Tony Bill, to hammy Ernest Borgnine, to implacable Jim

Brown. Thank goodness for the witty Patrick McGoohan as a cagey

British spy aboard to trap a Soviet spy. It’s corny fun, but for

some strange reason it holds its own against the much better “Hunt For

Red October” (1990). And it still strikes an emotional chord

—

punctuated by Michael Legrand's grand score. Go figure.

Bill Desowitz is a freelance writer and the editor of VFXWorld.com and a contributor to the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and Wired. He lives in Los Angeles.

Cover Images © Warner Home Video. All rights reserved