Making movies. Enjoying movies. Remembering movies.

THE BACKLOT

|

Posted April 21, 2005 |

|

|

By

Michael Coate

|

|

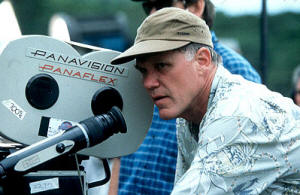

It is often said that movies are a visual storytelling medium. Although

there are a number of ways in which to become a director, today it seems

that many directors cut their teeth making music videos or television

commercials, both of which are very much a visual storytelling form. Or they

attend film school and make an impressive short film which lands them a

directing assignment. In the case of Joe Johnston, he made it to the

director's chair by way of another visual medium: drawing.

Johnston, a Texas native, got his start in the movie business after studying

graphic design and illustration at California State University Long Beach

and working briefly for Chuck Pelly Designworks, when he was asked to

contribute to a project that, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, would

revolutionize filmmaking... and film watching. The film: "Star Wars."

Johnston, one of the earliest and original members of what would eventually

be known as Industrial Light + Magic (ILM), contributed to "Star Wars" as an

effects illustrator, providing sketches and storyboards that would help the

crew develop and design their work. Following work on the TV series

"Battlestar Galactica," Johnston would re-join ILM as the operation

relocated to Northern California, and he would go on to contribute to some

of the most successful and highly-regarded productions of all-time: "The

Empire Strikes Back," "Raiders Of The Lost Ark," "Return Of The Jedi,"

"Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom." He would be awarded an Oscar for his

work on "Raiders." Published examples of Johnston's excellent work can be

found in books such as "The Art Of Star Wars" and "Raiders Of The Lost Ark:

The Illustrated Screenplay."

Following "Indiana Jones," Johnston enhanced his education by attending the

USC School of Cinema-Television at the urging of George Lucas. He would

broaden his resume by working as a production designer on two "Jedi"

spin-off telefilms: "The Ewok Adventure" and "Ewoks: The Battle For Endor."

He would also serve as a second unit director on "*batteries not included."

And following a stint as associate producer on "Willow," Johnston would move

on to the director's chair with the 1989 hit, "Honey, I Shrunk The Kids."

This was followed with the underrated "The Rocketeer." Next came "The

Pagemaster," "Jumanji," and, later, "Jurassic Park III." With these films,

Johnston proved that he could manage complex, large-scale, effects-filled

productions, no doubt his confidence gained through years of experience

working at ILM. But with "October Sky," he showed he could also make a film

that was less effects and more character driven. His latest film was the

widescreen epic, "Hidalgo."

During the post-production phase of "Hidalgo," Johnston took some time to

discuss his work and approach to filmmaking.

Michael Coate, From Script

To DVD: Has the introduction and success of the DVD format affected your

approach to filmmaking?

Joe Johnston: Not that I'm aware of. And now that you've mentioned

it, I'm going to be extra vigilant to see that it doesn't. I don't know how

it would, unless I was working on something that I knew was going

direct-to-video. As long as films will be first shown to the public in movie

theatres, in the format they were filmed in, I don't see why the DVD format

should influence their production. For one thing, the DVD format doesn't

require modifying an approach to filmmaking. Movies already make the

transition to disc easily, with a minor speed bump called the pan-and-scan.

The digital revolution is bringing some wonderful new tools and technologies

to the hands of filmmakers, but until there's a reason to do otherwise, I

still want to make films first, DVDs later.

The next big leap that digital will bring will be in exhibition, which

hasn't made a conceptual technological advance since the birth of the

industry. Don't get me wrong, film exhibition has made great improvements in

quality of image and sound, but it still involves sprockets grabbing

perforations and dragging the film in front of a red-hot bulb, behind a lens

that must be monitored for focus. Film still has to be reeled up and boxed

in heavy cans, shipped all over the country to the theatres where an

employee, who we truly hope cares about what he's doing, splices the reels

together, hopefully in the right order onto a platter where the film lives

for the run of the show, after which it's broken down and shipped off to

another theatre. Imagine being able to pop a disc in the mail or better yet

broadcast the signal to a thousand theatres simultaneously where the image

is always in perfect focus and the sound crystal clear.

That's the future of exhibition, but until it's a reality, moviegoers should

demand optimum quality when they pay their inflated ticket prices. Sixteen

foot lamberts is the standard level of projection light. Some theatre owners

turn it down to twelve and below because it makes the bulbs last longer. If

you've ever been in a second-run house in the suburbs of the heartland you

know what I'm talking about. No filmmaker wants to see his work shown and

heard in less than perfect conditions, but it's up to the all-powerful

audience to do anything about it. Complain.

FSTD: Can you comment on the recent 50th anniversary of the many

widescreen and multichannel sound processes, the widescreen revolution? Is

there any importance or noteworthiness to this occasion, or are these things

so common today that they are taken for granted?

| "I like to direct like a tour guide rather than a dictator." |

Johnston: Improvements

in technology are always important for those working with it, but I think

it's pretty much taken for granted by the moviegoing audience, as it should

be. Technology, as marvelous and enabling as it is, is just another tool to

help tell the story. Technology or any other tool shouldn't start to dictate

aspects of the storytelling process, except where they're invisible. If a

great film works in Imax, it should work in Super-8. As filmmakers, we're

less successful when audiences are "taken out of" the film by the man behind

the curtain. An example of this is Garrett Brown's Steadicam. It's a

wonderful invention. It allowed filmmakers to get the camera in places where

dolly track couldn't go: through crowded streets or up flights of stairs. It

became such a convenient timesaver that some directors started using it to

shoot entire movies, whether or not the floaty, somewhat spontaneous and

energetic quality it provides was the right choice for the material. I think

the key here is not to fall in love with the toys. Use what works best for

what you're trying to say.

FSTD: You've directed films in both "flat" ("Honey, I Shrunk The

Kids," "The Pagemaster," "Jumanji," "Jurassic Park III") and "scope" ("The

Rocketeer," "October Sky," "Hidalgo") formats. How do you select which

format to use? Do you prefer one aspect ratio over another, or do you choose

on a title-by-title basis?

Johnston: I definitely choose on a title-by-title basis, but it's

pretty much a gut reaction kind of thing. From the beginning, "The

Rocketeer" felt like a playful California postcard kind of movie, with

racing planes zooming across the frame, and long limousines and burning

zeppelins. You know, the typical 1930s California. I think the fact that the

material was based on a graphic novel probably influenced my choice to go

widescreen with it. I wanted the extra room to play around in.

|

With "October Sky," I didn't

decide to shoot it widescreen until after I'd scouted all the locations. At

first read it seemed like a 1.85:1 film, being a story that's about (at

least superficially) a bunch of guys shooting rockets into the sky, and

utilizing key visual elements like towering coal tripples. But after I'd

experienced the amazing landscapes of eastern Tennessee that the story would

unfold in, I decided to go widescreen so I could more easily place the

events and characters into the world and allow their surroundings to always

be a visual presence in the frame. The audience is hopefully conscious of

the physical world of the film without being distracted by it.

On "Hidalgo," there was never any doubt that this was a widescreen film. If

ever a combination of story and visual elements were made for widescreen,

this was it. The widescreen format allowed us to more effectively dramatize

a key aspect of the story, that of the stranger in a strange and hostile

land, tiny and insignificant, lost in the terrible beauty of this alien

environment. The director of photography, Shelly Johnson, took full

advantage of the unique creative freedom that widescreen allows and pushed

the visual envelope at every opportunity.

I'm a fan of the widescreen format because it seems more natural to me.

Humans, with their forward-facing binocular vision, see the world in

widescreen all the time. It's actually pretty similar in proportion to a

2.35:1 image on a big movie screen. I think this is why widescreen films

have a headstart in getting the audience to suspend their disbelief and get

drawn into the world unfolding on the screen.

FSTD: Of the films you've made in "true" widescreen, they've been

shot anamorphically, as opposed to spherically in Super-35. The majority of

widescreen films today are done in Super-35. Do you have a preference for

anamorphic origination and, if so, can you elaborate on why?

Johnston: I haven't worked in Super-35 so I can't speak from

experience, but Super-35 does not utilize all the available film area,

taking the 2.35:1 format out of the middle band of the frame, leaving unused

area above and below. Anamorphic uses all the available area, squeezing the

image to fit it into the 35mm frame and unsqueezing it with a similar lens

in projection. I feel I'm getting better resolution, a better quality image,

by using the entire frame. The disadvantage to anamorphic is the limited

selection of lenses, with a little less freedom on the close-up end of the

spectrum, but once you're used to what you have, it doesn't feel like a

restriction at all. Beautiful films have been shot in both formats and in

all honesty, the ultimate differences in image quality are probably

negligible. The anamorphic process also causes a slight "bowing"

imperfection, an artifact of the squeezing of the image most noticeable in

the pans, that I find pleasing.

|

FSTD: As a director,

do you tend to focus working closely with your actors, or do you prefer to

get more involved with technical matters such as working with the camera

crew on image composition and lighting and, later, with video transfers?

Johnston: First of all, I don't consider composition to be in any way

technical. It's about as creative a process as you can experience. Image

composition can add a level of storytelling that nothing else can. Where the

camera goes and what it sees are as basic as it gets.

I enjoy working with actors the most because it's the part of the process

that most defies definition, and honestly, the part I want the least control

over. I like to direct like a tour guide rather than a dictator. Acting is

the most personal of the filmmaking crafts, and one of the director's

primary responsibilities is to create an environment where talented actors

can feel free to push themselves to their personal limits. Movie magic takes

many forms, but I'm constantly fascinated and amazed when I see a moving

performance. One of the greatest gifts a director is given is being allowed

to be the first audience, who can then guide and shade the performance for

every audience to come after.

Like all directors, I want input into every aspect of the filmmaking

process. A feature film director is creating a world that doesn't really

exist and everything that finds its way through the lens onto film is a part

of that non-existent world and has the potential to have an effect on an

audience. It's crucial that the process be controlled.

Once the frontloaded decisions are made I like to hand off as much

responsibility as I possibly can. Shelly Johnson and I have similar taste in

composition and camera movement, so I have complete trust in his decisions,

but it's a team effort and we're all on the playing field all the time.

Where I like to get involved in the technology is when I see an opportunity

to use it to tell a better story. One amazing piece of technology that I

rely on heavily is the Technocrane. It's made more fluid, flexible camera

moves available and has often saved precious shooting time by making dolly

track unnecessary. There are lots of tools that can save time (which is

money) and lots that can let you be more creative. But there are few that,

like the Technocrane, lets you do both. I'd like to have one of my own.

FSTD: If you are involved with video transfers, can you offer some

thoughts on pan-and-scan presentations of your films in particular and all

films in general?

Johnston: Nobody loves a pan-and-scan, but it's the reality of the

business. Some films make more [money] in their video or DVD release than

they do in theatrical. The problem for the filmmaker is in the public

perception that they're being cheated by "widescreen" because the entire TV

screen isn't filled with image. The opposite is true. With widescreen

they're seeing the film as it was meant to be seen. They truly are being

cheated when they buy or rent the badly-named "fullscreen" version of the

film, but they seem to be resistant to accepting that reality. The world's

largest retailer of VHS, Wal-Mart, will not sell a widescreen movie on tape.

So, who needs to get educated, the consumer or the board of directors? When

all televisions are widescreen, will people complain about the old

"fullscreen" versions not filling up the sides of the screen? Let's hope so.

I assume, perhaps incorrectly, that the pan-and-scan "fullscreen" version is

primarily for VHS and that DVD viewers are the letterbox fans.

On rare occasions, you can

improve a particular shot in the pan-and-scan by forcing the viewer to focus

on a particular visual element that they may not have noticed in the

widescreen. But in general it's a compromise, so all we can do as filmmakers

is make it the best compromise it can be.

My least favorite pan-and-scan was "October Sky" because I felt I was

depriving the viewer of the reason I decided to shoot it widescreen. I felt

that the power of the harsh environment was diluted. The brooding and

melancholy blue-collar coal town's impact in telling the story was much

reduced. "The Rocketeer" pan-and-scan suffered from too much panning, trying

to get everything I felt was important into the picture. We actually did

pan-and-scan cuts, from one side of the screen to the other. It was my first

pan-and-scan and the most frustrating because I hadn't learned that less is

more in a pan-and-scan.

I just finished the pan-and-scan for "Hidalgo" and I was very happy with the

way it turned out. I would always recommend the widescreen version, of

course, but as pan-and-scans go, "Hidalgo" was the best I've seen.

Some of the older widescreen films that were panned-and-scanned when the

process was new are truly godawful. I'd love to see some of those films,

some regarded as classics, re-panned-and-scanned with a talented technician

at the controls. Of course, I'd much rather see them released only in

widescreen.

FSTD: How important a role does sound (namely, multichannel surround

sound) play in the effectiveness of a movie presentation?

Johnston: Sound plays a tremendously important role in presentation,

but like all other bags of tricks, it should only be an accessory to telling

the story. A talented sound designer can find ways to make sound evoke

feelings that pictures can't. But the key here is subtlety and restraint. If

every sound goes whirling around the theatre's surround sound system, the

audience gets tired of it and it loses its impact. If you put one or two

choice sound moments in the surrounds, it can have a shocking and memorable

effect.

|

|

|

|

Joe Johnston Feature Film Directing Filmography (Source:

IMDb)

Hidalgo (2004)

Jurassic Park III (2001)

October Sky (1999)

Jumanji (1995)

The Pagemaster (1994; live-action sequences)

The Rocketeer (1991)

Honey, I Shrunk The Kids (1989)

Additional Credits

The Adventures Of Young Indiana Jones: Spring Break Adventure (1999;

Director)

The Iron Giant (1999; Iron Giant Designer)

The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992; Director: "Princeton, February

1916")

Always (1989; Aerial Sequence Designer)

Willow (1988; Associate Producer)

*batteries not included (1987; Second Unit Director/Production Manager)

Howard The Duck (1986; Ultralight Sequence Design)

Ewoks: The Battle For Endor (1985; Production Designer)

The Ewok Adventure (1984; Production Designer)

Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984; Second Unit Art Director)

Return Of The Jedi

(1983; Visual Effects Art Director)

Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981; Visual Effects Art Director)

The Empire Strikes Back (1980; Visual Effects Art Director)

Battlestar Galactica (1978-79 TV series; Effects Illustrator and Designer)

Star Wars (1977; Effects Illustrator and Designer)

Photo Credits: Yahoo! Images; Touchstone Pictures and "Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects" by Thomas G. Smith, Ballantine Books, 1986