Making movies. Enjoying movies. Remembering movies.

|

|

|

|

Related Articles:

The Three Fathers of Cinema & The Edison/Dickson Experiment

Interpreting The Sound and The Theory

|

Posted January 28, 2005 |

|

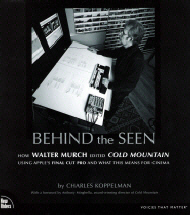

Behind The Seen: How Walter Murch Edited “Cold Mountain” Using Apple's Final Cut Pro And What This Means For Cinema A Book Review |

By

William Kallay

If you’re now a regular visitor to this site, you will no doubt be familiar with Walter Murch. He features his theory of the Three Fathers Of Cinema in his own fascinating story, and he also is featured in the article, Interpreting The Sound And The Theory. So it should come as no surprise that when a new book is written about him and his work, it is my sworn duty, not only an admirer of his work, but as an admirer of cinema, to write about it.

Outside of Murch’s own “In The Blink Of An Eye” (2nd Edition, 2004), “Behind The Seen: How Walter Murch Edited ‘Cold Mountain’ Using Apple’s Final Cut Pro And What This Means For Cinema” by author Charles Koppelman, is perhaps the best book about editing ever written. This is an intriguing account on the making of Anthony Minghella’s adaption of “Cold Mountain” (2003), and Murch’s acceptance of using Apple’s Final Cut Pro software program to edit the film.

To be honest, there

haven’t been a lot of popular books written on this subject of the science

of editing a motion picture. In the context of subjects about making

movies, editing, unfortunately, is usually towards the end of the book rack

of popularity. Directors and actors usually take center stage. But in the

case of Walter Murch, his stories and his books are held in high regard. Of

course, this isn’t to say that a number of other editors don’t deserve

recognition and high praise. In the world of movies, though, Murch is

considered one of the greats.

”Behind The Seen” is a carefully written and well-documented account of how

“Cold Mountain” was edited. People familiar with Murch should already know

that his editing of picture and sound is impeccable. He’s applied not only

a science to editing, but human emotion to how a motion picture will affect

an audience. Editing for Murch isn’t merely about cuts; it’s about how a

movie feels.

But one of the other fascinating aspects about this book is the breakdown of how Final Cut Pro was introduced into the world of professional filmmaking. Used mainly in consumer and industrial video editing, FCP (as it’s sometimes called) was Apple’s answer to other software programs in use, like Adobe’s Premiere and Avid. At the time of “Cold Mountain,” FCP wasn’t considered to be useful or functional for feature film editing.

What is intriguing, and Koppleman builds a good story here, is the interplay between Murch, his assistant editor, Sean Cullen, the principals of Digital Film Tree (a digital post-production company), and Apple Corporation. Murch was interested in using FCP on “Cold Mountain.” Previously, he had used Avid, but wasn’t entirely pleased with that system’s reliability. But Apple was reluctant to hand over the keys to its software, so-to-speak, to Murch, or anyone else in the professional film community. FCP simply wasn’t ready for the big leagues as far as the company was concerned. Koppleman illustrates that Apple perhaps didn’t know they were dealing with one of the most respected people in the film industry. Murch subtly persisted in getting Apple to work out the kinks and make the system work for him. Cullen made sure that Digital Film Tree fixed any glitches in the software that would slow Murch down. Together, all parties were making strides in possibly developing a new alternative in feature film editing with FCP.

The book delves into the friendship and working relationship between Murch and Minghella. Copious emails were exchanged during the entire production of the film. Readers are given an inside look at how a detailed and organized editor like Murch provides valuable feedback to a talented director like Minghella. Theirs isn’t a case of a director simply handing off the film to an editor and saying, “Cut it.” The work between Murch and Minghella is complimentary.

Personal journal entries from Murch are included in “Behind The Seen,” and these are short and fascinating insights into his mind during the editing process. What we get is not more of what he thinks about when he’s editing, but more of the man himself. I found it sweet, (but not sappy) that he talks about meeting his wife, Aggie, upon arriving in London, and he makes note of his affection and love for her and his family through these notes. This is not something you normally read in books about editing! We also get insight into some of his routine of taking a long run through the hills around his secluded home in Northern California, early morning swims, and some of his theory on film and its relation to an audience. Despite his immense mastery of film, Murch comes across in the book as a gentleman with a sense of humor, sense of history and a sense of brilliance.

The art of editing, of course, is presented in the book, but not in detail like in Murch’s “In The Blink Of An Eye.” I believe the focus is more on Murch the person and the story of using FCP as a feature film editing tool. This is where the book excels. None of the book lags and it’s a constant “page turner.” Koppelman breaks down the entire process from when the film is shot, to when it’s digitized into an Apple, to when it’s edited, to the final cut and test screenings.

Koppleman’s book on Murch’s editing of “Cold Mountain” isn’t simply about film editing, but of an intriguing journey from script-to-screen. “Behind The Seen” is recommended reading for anyone intersted in the art of making movies, and it’s especially recommended for those who are fans of Murch’s work.

“Behind The Seen: How Walter Murch Edited ‘Cold Mountain’ Using Apple’s

Final Cut Pro And What This Means For Cinema”

By Charles Koppelman

Softcover: 360 pages

2004

$39.99

Book Cover Photo by Steve Double/RETNA